The Structural Shift from Efficiency to Security

Modern economic security depends less on raw resource extraction and more on the sophisticated midstream processing and digital-physical infrastructure that govern the geopolitics of global supply chains. For decades, the global trade system was optimized for a single variable: cost. This led to the “Just-in-Time” model, where inventory was a liability and efficiency was the highest virtue.

Recent systemic shocks have revealed that this focus on efficiency often comes at the expense of resilience. When a single node in a lean system fails, the effects cascade through the entire network. This vulnerability has forced a reappraisal of how global trade is structured, moving from a model of hyper-efficiency to one of strategic durability.

Transitioning from Just-in-Time to Just-in-Case Models

The shift toward “Just-in-Case” logistics represents a fundamental re-engineering of how goods move. This transition moves away from lean, brittle chains toward buffered, redundant systems. In this new framework, holding surplus inventory and diversifying supplier bases are no longer viewed as inefficiencies, but as essential insurance policies against geopolitical instability.

This transition requires significant capital expenditure. Companies must build or lease more warehouse space and manage increasingly complex procurement networks across multiple regions. To handle this complexity, firms use visibility platforms like Project44 and FourKites. These tools allow logistics managers to see beyond their immediate suppliers and monitor the health of the entire network. The goal is no longer just to minimize the cost of a single transaction, but to ensure the continuity of the entire system under stress.

The Role of National Security in Commercial Logistics

Commercial logistics is now inseparable from national security. Governments view the “securitization” of trade as a primary objective, leading to the formation of trade blocs where shared values and security guarantees take precedence over the lowest market price. When a supply chain is securitized, it is no longer governed solely by market forces; it is directed by strategic intent and state-backed incentives.

This shift introduces new layers of regulation and oversight. Trade agreements that once focused on tariff reduction now include provisions for data security, labor standards, and environmental compliance. These requirements serve as a filter, ensuring that the components of a nation’s critical infrastructure are sourced from “trusted” partners. The result is a fragmented global market where the flow of goods is determined as much by diplomatic alignment as by economic demand.

Strategic Vulnerabilities in Critical Mineral Processing

While mining often receives the most attention, the primary chokepoint in the geopolitics of global supply chains is not the extraction site. It is the midstream processing—the chemical and thermal steps required to turn raw ore into high-purity materials. A country may have vast lithium deposits, but if it lacks the specialized facilities to synthesize battery-grade lithium hydroxide, it remains a peripheral player in the value chain.

The Gap Between Extraction and Midstream Refining

The technical barriers to midstream refining are substantial. Refining critical minerals like cobalt, nickel, and rare earth elements involves energy-intensive chemical processes that produce significant environmental externalities. Historically, many Western nations outsourced these processes to regions with lower environmental standards and labor costs. This created a geographical decoupling: the West became the consumer, while a small handful of nations became the indispensable processors.

This decoupling has created a systemic vulnerability. If the midstream nodes are concentrated in a single jurisdiction, the global production of end-use technologies—from electric vehicle batteries to fighter jets—is subject to the export policies of that jurisdiction. This explains why “resource nationalism” is increasingly focused on the refining stage. Nations are now moving to build domestic refining capacity to ensure that their raw materials can be converted into usable components without relying on adversarial or unstable third parties.

Monopolistic Control of High-Purity Material Synthesis

Beyond basic refining, the challenge of material synthesis remains. High-performance semiconductors and advanced batteries require chemical precursors of extreme purity. These precursors are often produced by a very small number of specialized companies. Control over these chemical ingredients provides a lever of influence that is often more effective than traditional trade embargoes.

If a manufacturer cannot source the specific phosphoric acid, precursor salts, or specialized gases required for their process, their entire multi-billion dollar facility remains idle. These “micro-dependencies” are difficult to map and even more difficult to replace. They represent the most granular level of the geopolitics of global supply chains, where the control of a single proprietary chemical formula can stall an entire industry.

Digital-Physical Infrastructure: The Invisible Layer of Control

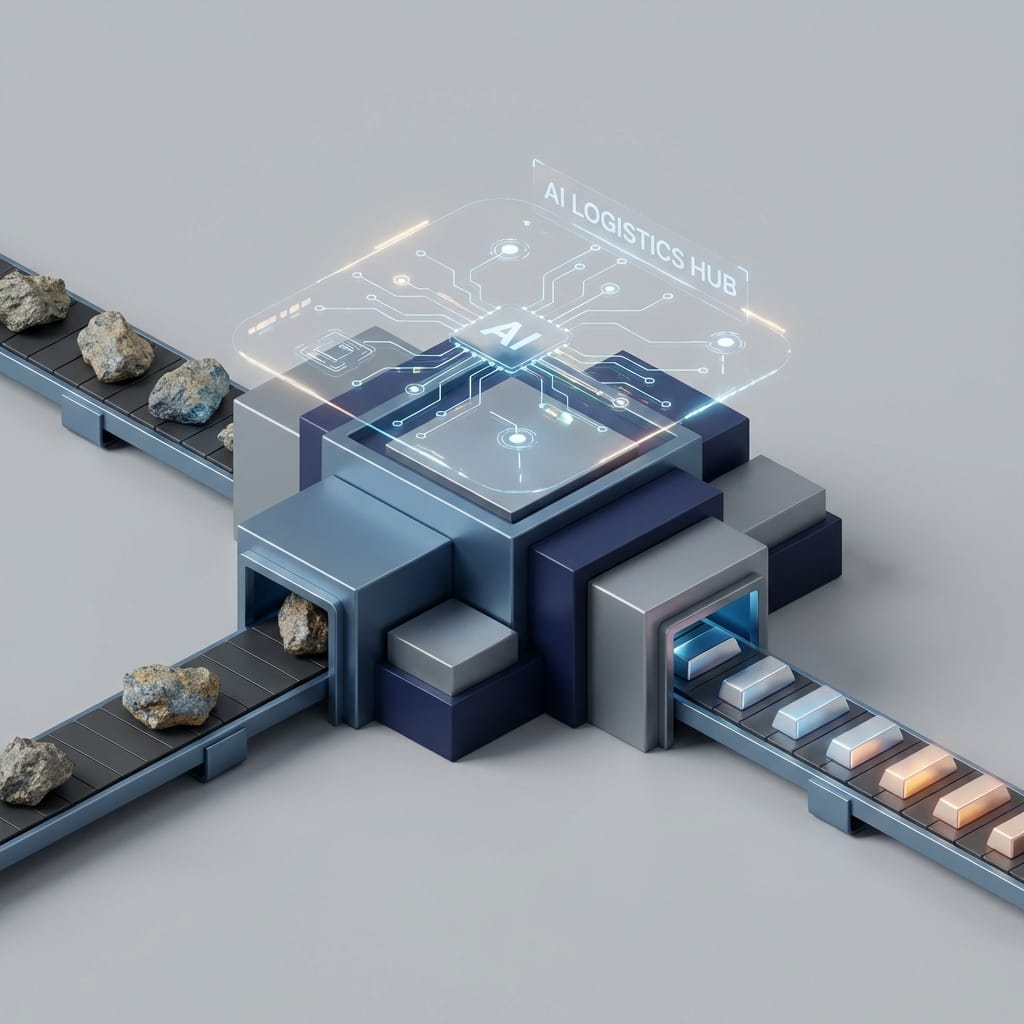

The modern supply chain is not just a series of ships and trucks; it is a massive, distributed data system. The integration of digital-physical infrastructure—specifically automated ports and AI-driven logistics—has created a new layer of control. When examining the geopolitics of global supply chains, we must consider who owns and operates the software that manages the flow of information across these physical assets.

Sovereignty over Automated Ports and Maritime Data

Modern port terminals are managed by Terminal Operating Systems (TOS). These systems coordinate the movement of millions of containers, optimizing crane movements, berth assignments, and gate operations. However, a TOS also provides real-time visibility into what is moving, where it is going, and who owns it. If a single entity or state-affiliated company provides the TOS for dozens of major global ports, they gain a massive information advantage.

Companies like DP World and Maersk are no longer just shipping companies; they are integrated logistics providers that manage the physical and digital interfaces of trade. Sovereignty in 2026 is increasingly defined by the ability to control these data flows. Ensuring that maritime data is not used for economic espionage or strategic coercion has become a priority for coastal nations seeking to protect their commercial interests.

AI-Driven Logistics and Information Asymmetry

AI-driven logistics platforms, such as Flexport, aggregate data from thousands of sources to predict disruptions and optimize routes. While these tools provide value to shippers, they also create a new form of information asymmetry. The entities that control these platforms can see patterns of trade and vulnerabilities in real-time, often before the participants in the supply chain are aware of them.

This “macro-visibility” is a potent geopolitical asset. It allows for the anticipation of economic shifts and the targeted application of trade pressure. If a state can identify which specific components are most likely to cause a production bottleneck in a rival nation, it can calibrate its export controls for maximum impact. In this environment, data is not just a tool for efficiency; it is a prerequisite for strategic autonomy.

“Control of the physical port is the lock; control of the logistics software is the key. You cannot have one without the other in a modern economy.”

Economic Corridors and Sovereign Infrastructure Investment

The competition for transcontinental trade routes is the most visible expression of supply chain geopolitics. Nations are racing to build “economic corridors”—integrated networks of ports, railways, and pipelines that bypass traditional maritime chokepoints or connect landlocked resource-rich regions to global markets.

The Competition for Transcontinental Trade Routes

Western-led initiatives, such as the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), and various Eastern-led infrastructure projects are competing to define the trade routes of the next several decades. These are not merely construction projects; they are strategic alignments. When a nation accepts financing for a deep-water port, it is often entering a long-term technological and regulatory ecosystem.

The standards used for rail gauges, the software for customs clearance, and the security protocols for data networks all create a “path dependency” that favors the lender. These technical standards act as a form of “soft power,” locking nations into specific trade orbits. Once an infrastructure network is built using a specific nation’s technology, switching to a competitor’s system becomes prohibitively expensive.

Infrastructure Financing as a Tool for Diplomatic Alignment

Infrastructure financing has become a primary tool of economic statecraft. In some cases, debt-to-equity conversions allow the financing nation to take an ownership stake in critical assets if the borrower defaults. This “infrastructure-for-sovereignty” trade-off can fundamentally alter the geopolitics of global supply chains by giving foreign powers direct control over key nodes in another nation’s territory.

For policymakers, the challenge is to secure the necessary investment for development without ceding control over the very infrastructure that enables their economic participation. This has led to the rise of multi-lateral financing frameworks where risk is shared among several nations and private investors. These frameworks aim to provide a more transparent alternative to bilateral deals that may carry hidden strategic costs.

The Mechanics of De-risking and Strategic Autonomy

To counter these vulnerabilities, many nations are pursuing “de-risking” strategies. De-risking is not about total decoupling—which is likely impossible in a deeply integrated global economy—but about reducing dependency on any single adversarial node, particularly in the midstream and digital layers.

Diversification Strategies and Friend-Shoring Frameworks

The concept of “friend-shoring” involves moving critical supply chain segments to countries that share similar values and security interests. This is a move toward “trusted networks.” For example, the United States and its allies are working to build a diversified battery supply chain, incentivizing the development of refining facilities in Australia, Canada, and the EU. This is not necessarily the most cost-effective solution, but it is the most strategically sound for those concerned about resource security.

These networks rely on transparency and shared standards. By aligning their regulatory environments, partner nations can ensure that goods move across borders with minimal friction, even while maintaining high standards for security and environmental protection. This creates a “protected” market that is insulated from the volatility of more centralized systems.

Regulatory Tools and Export Control Mechanisms

Governments are also using regulatory tools to protect their supply chain sovereignty. This includes investment screening to prevent foreign entities from acquiring critical infrastructure and export controls to limit the transfer of sensitive technologies, such as advanced lithography machines used in chip manufacturing. These mechanisms are designed to maintain a “technological moat” around the most critical components of the modern economy.

These controls are often applied with surgical precision. Rather than banning all trade with a rival, a nation may restrict only the specific tools or materials required to produce the next generation of high-end technology. This allows for continued economic engagement in non-sensitive sectors while protecting the strategic advantages that underpin national security.

Future Trajectories of Supply Chain Sovereignty

The long-term environment of the geopolitics of global supply chains will likely be shaped by technological substitution. As certain minerals become strategic chokepoints, the incentive for material innovation increases. We see this in the development of sodium-ion batteries, which could reduce the reliance on lithium and cobalt, and in the growth of “urban mining” and advanced recycling technologies.

Technological Substitution and Material Innovation

If material science can engineer around scarcity, the leverage of nations that control specific mineral deposits or refining processes may diminish. However, new technologies usually bring new dependencies. For instance, moving to a hydrogen economy would require new types of catalysts and membrane materials, shifting the geopolitical focus to a different set of critical elements and processing techniques.

The “material basis” of geopolitics is dynamic. As industries transition to new energy sources and manufacturing methods, the maps of critical minerals will be redrawn. This creates a continuous cycle of discovery, exploitation, and substitution. For nations to remain resilient, they must invest in research and development that allows them to adapt to these shifts before they become vulnerabilities.

The Resilience of Interdependent Economic Systems

Ultimately, the challenge for global leaders is to balance the requirements of national security with the undeniable benefits of an integrated global economy. Total strategic autonomy is an expensive and likely unachievable goal for most nations. The most resilient systems will not be those that are entirely self-contained, but those that are part of a diverse, transparent, and redundant network of “trusted” partners.

Understanding the hidden layers of control—from chemical precursors to port operating systems—is the first step in navigating this new era of global trade. As the world moves toward a more fragmented and securitized model, the ability to map these dependencies will determine which nations thrive and which remain vulnerable to the next systemic shock. Resilience is built through clarity, not isolation.