As game complexity outpaces manual production capacity, the core challenge of development is shifting from the creation of static assets to the orchestration of dynamic, intelligent systems. Successfully implementing generative AI game development workflows allows studios to move beyond the limitations of manual labor and into the realm of algorithmic orchestration.

The Evolution of Game Development Pipelines

Historically, game development has relied on a “Fixed Asset” production model. In this paradigm, every 3D model, texture, and animation is a discrete file created by an artist, exported to a specific format, and placed manually within a scene. This creates a linear relationship between the size of a game world and the number of man-hours required to build it. As the industry moves toward expansive environments, this linear model becomes financially and logistically unsustainable.

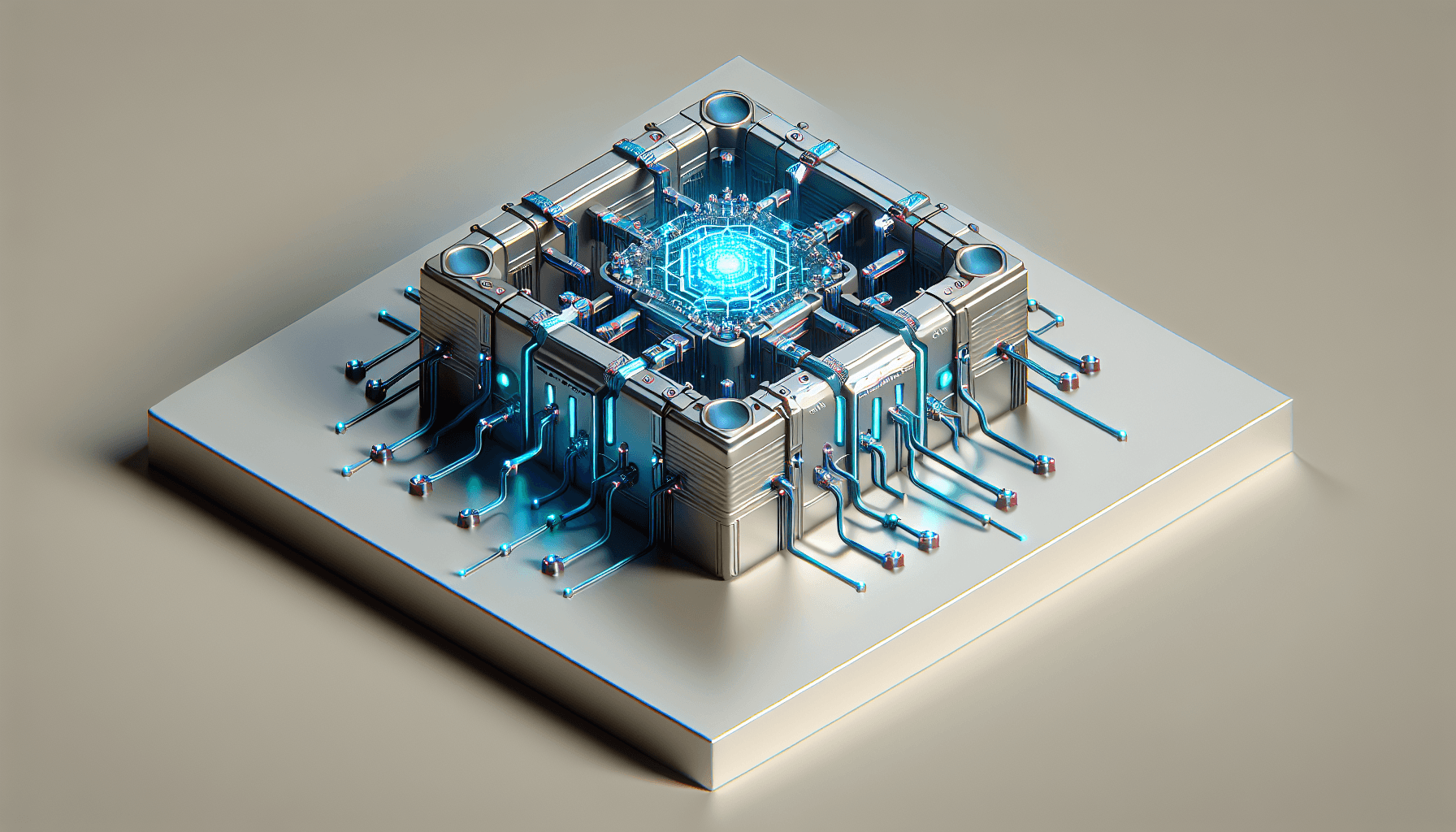

The transition occurring in 2026 is a move from fixed assets to “Dynamic Logic” pipelines. Instead of storing a static rock mesh, the engine stores the logic of what a rock should look like in a specific biome. This shift bypasses the traditional scene graph—the hierarchical structure that tracks every object in a game world—which often becomes a computational bottleneck in massive environments.

By using generative models, studios can move toward a system where the world is synthesized in real-time based on high-level parameters rather than being loaded from a hard drive. This reduces the storage footprint on the user’s device while allowing for a degree of environmental variety that was previously impossible to hand-craft. The engine effectively becomes a translator between the developer’s intent and the rendered reality.

Streamlining Asset Production with Generative Models

The most immediate application of these technologies is the automated game asset pipeline. In the early stages of production, the “time-to-prototype” is a critical metric for determining if a concept is viable. Using tools like Stability AI or Midjourney, concept artists generate hundreds of iterative designs in the time it previously took to sketch one.

This process is not about replacing the artist, but about providing a higher-bandwidth input for creative direction. When an art director can see fifty variations of a character’s armor in minutes, the decision-making process moves faster. The human element remains essential for curation, ensuring that the generated outputs align with the game’s specific aesthetic and narrative goals.

Moving from 2D to 3D, developers are increasingly adopting text-to-3d workflows and Neural Radiance Fields (NeRFs). These technologies allow teams to convert simple descriptions or a series of 2D photographs into high-fidelity 3D geometry. While the topology of AI-generated meshes often requires automated “retopology” to be game-ready, the initial synthesis saves days of manual modeling, ensuring stylistic consistency across thousands of unique objects.

The Shift to Dynamic Level and World Generation

Traditional level design is a meticulous process of “gating” and “pathing,” where designers carefully control where a player can go and what they can see. However, as generative AI game development integrates into the core engine, environment synthesis begins to respond to player intent. If a player explores a mountain range that was previously intended to be decorative, a dynamic logic pipeline can generate the geological features, flora, and collision data for that area on the fly.

This is distinct from the procedural content generation seen in earlier titles. While procedural systems use fixed rules and noise functions to shuffle existing assets, generative synthesis uses learned patterns to create contextually aware environments. A procedural system might place a tree on a slope based on a random seed; a generative system understands that a tree on a steep slope needs a specific root structure and lean to look “natural.”

The technical requirement for this shift is significant. It requires a move toward real-time world synthesis where the engine acts less like a playback device and more like a live renderer of mathematical probability. This change allows for “infinite” play spaces that maintain a high level of detail without requiring the developer to manually place every blade of grass or jagged stone.

Transforming NPC Interactions and Narrative Depth

One of the most visible shifts is the move toward AI-powered NPCs. For decades, non-player characters have been limited by branching dialogue trees—pre-written scripts that the player navigates like a menu. This is a “Fixed Asset” approach to storytelling that inherently limits player agency. By integrating Large Language Models (LLMs), developers can create storytelling systems where characters respond to specific actions and words in a context-aware manner.

Using platforms like Inworld AI, developers define a character’s personality, knowledge, and goals, allowing the model to handle the specific phrasing and delivery. This creates emergent gameplay, where two players might have entirely different narrative experiences based on how they interact with the world. One player might talk their way past a guard, while another might inadvertently offend them, leading to a completely different mechanical outcome.

The challenge here is implementing “narrative guardrails” to ensure the AI does not break character or violate the game’s lore. This requires a layer of deterministic logic—often called a “knowledge base”—that sits over the probabilistic nature of the LLM. The goal is to provide the illusion of total freedom while keeping the player within the bounds of the designed experience.

Technical Integration and Engineering Challenges

Integrating these models into existing engines like Unity or Unreal Engine presents significant engineering hurdles. The primary issue is inference—the process of running a trained model to generate an output. Running a high-parameter LLM or a 3D synthesis model requires substantial GPU resources, which are already in high demand for rendering graphics.

Developers must choose between two primary paths for generative AI game development:

- Local Inference: The model runs on the player’s hardware. This eliminates latency and cloud costs but limits the model’s complexity based on the user’s specific GPU and RAM.

- Cloud Inference: The model runs on a remote server. This allows for massive, high-fidelity models but introduces latency and recurring operational costs for the studio.

Furthermore, game engines require deterministic outputs. If a player returns to a generated location, it must look exactly as it did before to maintain immersion. Generative models are inherently probabilistic; they rarely produce the same result twice unless carefully “seeded.” Engineering teams must develop robust caching and seeding systems to ensure that the “Dynamic Logic” pipeline remains consistent across different play sessions and hardware configurations.

Strategic ROI for Generative AI Game Development

For studio executives, the return on investment in generative AI game development is found in operational scalability. In a traditional workflow, doubling the content of a game roughly doubles the cost in terms of payroll and time. With a generative pipeline, the marginal cost of additional content drops significantly after the initial system is built. This allows smaller teams to produce games with the scope of AAA titles.

There are also new revenue models to consider. When the world and characters react dynamically, player engagement typically increases. This longevity allows for deeper monetization strategies centered around unique, personalized experiences rather than generic asset sales. A player who has a unique relationship with an NPC is more likely to remain invested in the game’s world over a longer period.

However, studios must remain vigilant regarding the intellectual property framework. Ensuring that training data is ethically sourced and that the resulting outputs are legally protectable remains a high-priority risk management task. As legal precedents evolve, the ability to prove the “human in the loop” becomes vital for securing copyright over AI-assisted creations.

“The real revolution isn’t just cost-cutting, but the transition from ‘Fixed Asset’ pipelines to ‘Dynamic Logic’ pipelines, where the engine becomes a live creative collaborator.”

The Future of the System Architect

As these systems mature, the role of the game developer is undergoing a fundamental shift. We are moving away from being “content creators” who hand-craft every pixel and toward being “system architects” who design the rules and constraints within which the AI operates. The game engine is no longer a passive tool used to arrange assets; it is becoming a live collaborator that interprets human intent and executes it with algorithmic precision.

This transition does not signal the end of human creativity in gaming. On the contrary, it removes the repetitive labor that often leads to developer burnout. By delegating the rote aspects of asset creation and world-building to generative systems, designers can focus on the higher-level logic of game mechanics, emotional resonance, and systemic balance. The future of the industry belongs to those who can master the synthesis of human vision and machine execution.

For further exploration of the hardware requirements for these systems, NVIDIA provides documentation on AI integration for real-time graphics. Similarly, the OpenAI research pages offer insights into the foundational models that power modern narrative systems. Understanding these building blocks is the first step in migrating toward a dynamic development future.