The End of Native Resolution and the Rise of Reconstruction

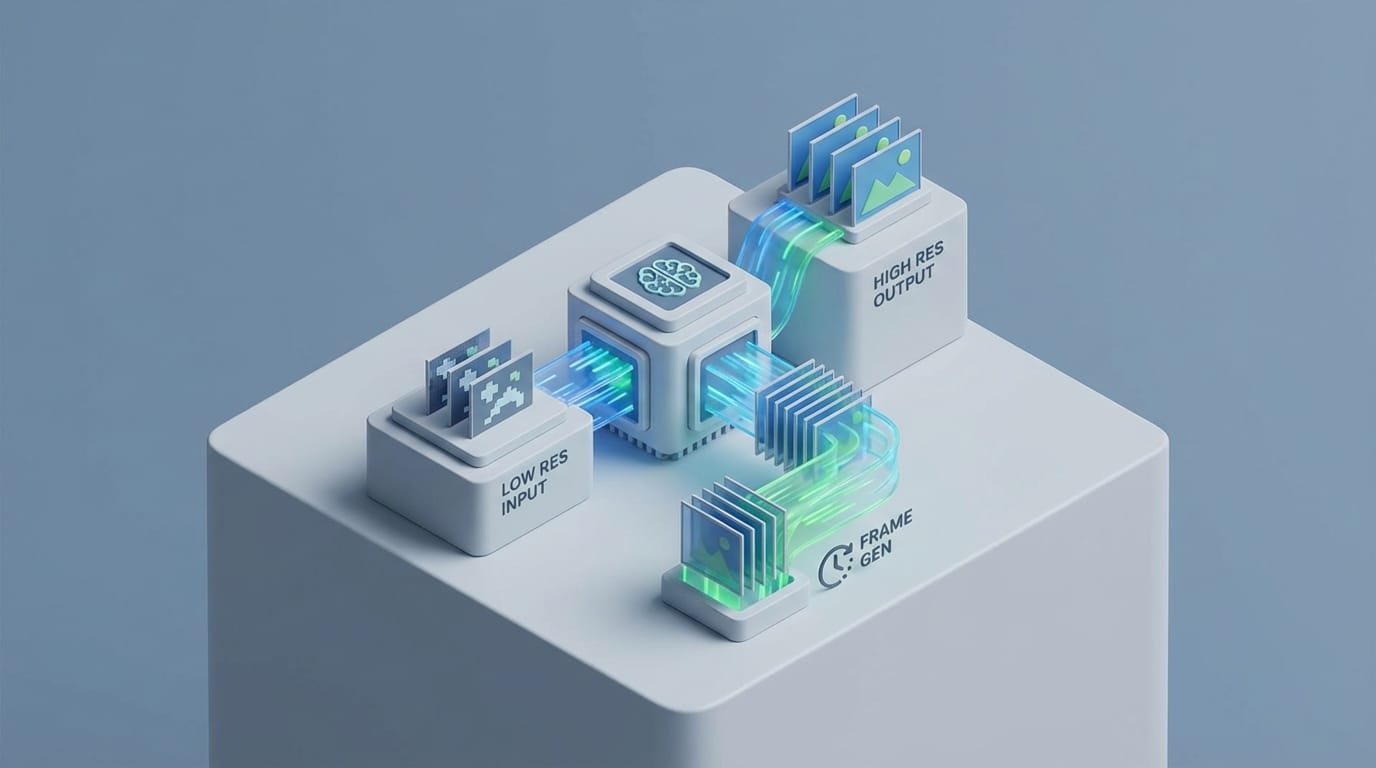

Thinking that more transistors alone will meet the need for 4K gaming ignores the shift toward neural rendering. To get past hardware limits, the industry now uses ai graphics upscaling as the main way to deliver sharp images without the high cost of native resolution. For decades, hardware makers tried to increase the power of the GPU by adding more shaders and higher clock speeds. We simply pushed more pixels to get a better picture, but as we reach the physical limits of chips and the heat limits of silicon, doubling power every two years is no longer easy. Moving from native rendering to smart reconstruction means we stop calculating every pixel and start predicting what they should be.

From Spatial Interpolation to Temporal Stability

In the early days of display scaling, we used simple spatial methods like bilinear or bicubic interpolation. These tools look at nearby pixels in one frame and average them to fill gaps, which often creates a blurry image that lacks fine detail. Modern reconstruction is different because it adds the element of time to the math. Temporal upscaling gathers data from several past frames to help build the current one. By using a jittered pattern, the engine draws the scene at a slightly different spot in every frame. This trick ensures that over a short time, the GPU sees every part of the image even if it does not draw it all at once.

This method builds a much more complete picture than any single frame could provide on its own. As the system gathers more data, it refines the edges of objects and smooths out textures. The result is a clean, sharp image that often looks better than a lower-resolution source stretched to fit the screen. Because the system tracks how objects move over time, it can also prevent the flickering that often ruins the look of thin lines or distant fences in a game world.

Why Brute Force Rasterization Hit the Hardware Ceiling

Native 4K rendering forces the GPU to calculate color and light for over eight million pixels many times per second. By 2026, the speed needed to move this much data across the bus has become a major hurdle. Increasing resolution further does not always make the image look much better, but it does make the hardware run much hotter. By rendering at a lower resolution and using AI to fill the gaps, we can use that saved power for complex effects like path tracing or better physics. The industry is leaving behind the old mindset where every pixel is a fixed math problem and is moving toward an era of smart rendering. We give the system the most important data and let a trained model build the final image, often with a level of clarity that exceeds the original source.

The Mechanics of Neural Network Training for AI Graphics Upscaling

The success of ai graphics upscaling depends on the quality of the neural network that drives it. Unlike old code that engineers wrote by hand, these models learn by looking at a low-quality image and comparing it to a perfect one. This training helps the system spot patterns, such as light reflecting off metal or hair blowing in the wind, so it can recreate those details from tiny amounts of data. The model learns to fill in the blanks based on millions of examples it studied during the training phase in the lab.

Supervised Learning on High-Resolution Ground Truths

To train a model like NVIDIA DLSS, engineers show the network millions of frames at 16K resolution along with 1080p versions. The network tries to turn the 1080p image into the 16K one, and if it fails, the system fixes the math inside the network. Over time, the model learns about shapes and light. This lets it rebuild edges and textures with great care and precision. This method works well to stop shimmering or pixel crawl on thin objects. Since the model has seen millions of wires and fences, it knows how to keep them steady across frames. It creates a result that stays more stable than native rendering, which can look rough when objects are smaller than a single pixel.

How Convolutional Autoencoders Predict Sub-Pixel Detail

A structure called a convolutional autoencoder drives this process. This design first shrinks the data to find the most important parts, then grows it back into a high-resolution format. It does not just guess a pixel color, but instead uses motion data and depth maps to see where an object was and where it is going next. Using special parts like Tensor Cores lets these tasks happen in less than a millisecond. Software tools can do similar work, but they often lack the speed to run complex models without losing the performance gains they were supposed to provide. These hardware units act like a fast lane for the complex math required to rebuild the image in real time.

Synthetic Frame Generation and the Optical Flow Challenge

Beyond making frames sharper, modern GPUs now create whole new frames that the game engine never made. This method, called frame generation, uses AI to put a fake frame between two real ones. This doubles how smooth the game looks, turning 60 frames into 120 without adding stress to the CPU. The system looks at the frame that just finished and predicts what the next one will look like before it even exists. This allows for a much smoother visual flow that makes movements feel more lifelike and fluid.

Analyzing Motion Vectors for Interstitial Frame Creation

To make a new frame, the GPU tracks how every pixel moves between two images. It blends this with game data that shows how 3D shapes move through the digital world. The AI then finds the best spot for every object in the middle of that time gap. It paints a new picture to fill the void between the two real frames. This is much better than the motion smoothing on TVs because the GPU knows the depth and motion of game objects. It can handle overlapping items and changing light without the heavy blur associated with older tech. The AI understands that a character moving in front of a tree requires a different calculation than a tree blowing in the wind.

The Latency Trade-off in AI Generated Motion

A big hurdle for frame generation is the delay it adds to the game. To make a middle frame, the GPU must wait for the next real frame to finish before it can find the midpoint. This means the image on your screen is slightly late. For pro players, this delay can feel like lag, making the game feel slow even if it looks fast. To fix this, makers use lag-reduction tools like Reflex or Anti-Lag. These systems sync the CPU and GPU to process your clicks as late as possible, which cuts the time between a mouse click and the result on screen. While it might not feel as fast as true high-speed rendering, most players will not notice the trade-off because the visual gain is so high.

Neural Rendering as the New Foundation of the Graphics Stack

The biggest change in 2026 is that AI is no longer just a final touch. In the past, we drew a frame and then used ai graphics upscaling to clean it up. Now, the whole system expects AI to do the heavy work at the end. This is the new era of neural rendering where the game engine and the AI work as a single unit. Instead of trying to render a perfect image from the start, the system creates a rough draft that the AI later turns into a masterpiece. This shift allows developers to push visual limits that were once thought to be impossible for home computers.

Moving AI from Post-Process Effect to Core Pipeline

Features like Ray Reconstruction show this change clearly. Path tracing shoots millions of light rays to make shadows and reflections, but it is often messy because we can only shoot a few rays per pixel. Instead of using old filters to fix the mess, we use neural networks to build the final image. In this model, the engine makes a rough and noisy draft of the scene. The AI then uses its training to turn that draft into a high-detail world. This allows for light and color that would be impossible to reach with old methods on current chips. By using the AI to solve the noise, we get the benefits of realistic light without the massive cost of calculating every single ray.

Bypassing the VRAM and Memory Bandwidth Bottleneck

As games look better, the need for memory and data speed grows fast. We are reaching a point where the size of memory chips and the power they use are becoming a problem for designers. AI upscaling works like a tool to shrink data. We store and move less data across the computer, and the AI grows it back into a sharp image right before it hits the screen. This allows games to run on hardware that would otherwise be too weak for such high quality. By moving the work from memory to AI units, we get past the physical blocks that have slowed down GPU growth. The old way of drawing every pixel is ending because silicon cannot keep up with our need for more detail.

DLSS vs FSR vs XeSS Architectural Differences

While the industry agrees on AI, the way each company does it varies based on their hardware. Each path shows a different idea about how many people can use the tech and what parts of the chip should do the work. Understanding these differences helps anyone trying to pick PC parts today. Some companies choose to lock their tools to their own chips, while others try to make them work for everyone. These choices affect how long a graphics card stays useful as new games come out.

Private Hardware vs Open Source Cross-Platform Approaches

NVIDIA’s DLSS needs special Tensor Cores to function. This hardware is built just for the math needed for deep neural networks. It handles hard jobs like thin leaves or fast smoke very well, but the catch is that it only works on NVIDIA cards. In contrast, AMD and Intel focus on more open paths. Their ai graphics upscaling tools work on almost any GPU, including consoles and older gear, by using standard parts of the chip. This means more gamers can enjoy the benefits of AI, even if they do not have the newest or most expensive hardware.

The Impact of Machine Learning Hardware on Final Image Quality

People often argue if special hardware makes a better image. In most cases, models that run on AI-specific chips can use more complex math. This often leads to a more stable image with less flicker on far-away objects. Software tools must strike a balance between the quality of the AI and the time it takes to run on the main part of the chip. If the AI takes too long, it defeats the purpose of trying to make the game run faster. But the gap is closing as software gets smarter. New standards are appearing to give makers a single path for all chips. While the hardware varies, we are moving toward a future where native resolution is an old term. It is being replaced by AI-driven images that let us see further and more clearly than silicon alone allows.