The Technological Shift in Traditional Childhood Play

Innovations in the evolution of smart toys are becoming invisible, shifting focus from screens to tactile, three-dimensional exploration. This marks a transition from toys that merely provide entertainment to systems that actively participate in a child’s developmental environment. By embedding logic directly into physical objects, designers are creating tools that prioritize presence over digital distraction.

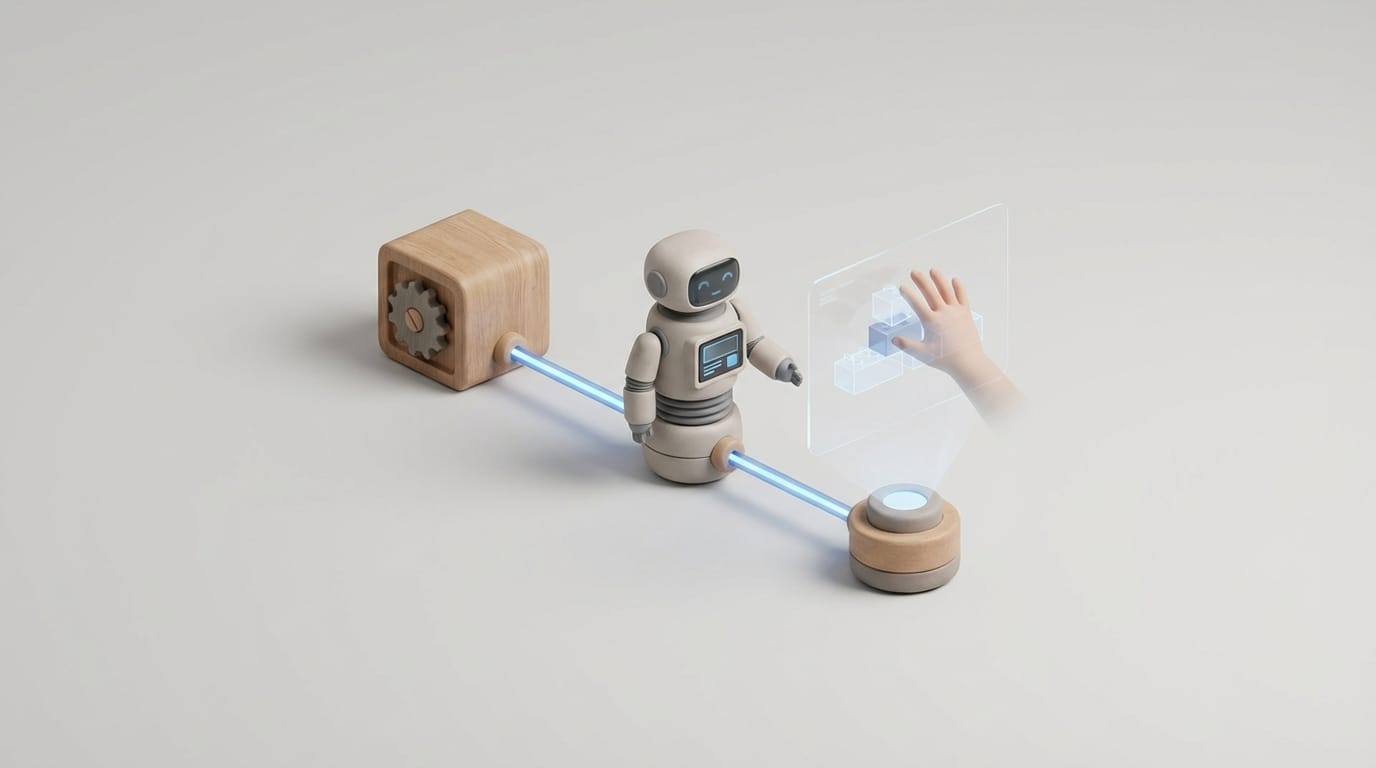

Defining the Smart Toy System

A smart toy is an embedded system consisting of three core components: sensors (input), a microprocessor (logic), and actuators (output). Unlike a traditional teddy bear, a smart toy operates through a feedback loop. It perceives a child’s action—such as a squeeze, a spoken word, or a change in orientation—and responds in a way that feels intentional.

This network of devices is often called the Internet of Toys (IoToys). It connects physical objects to local or cloud-based networks, allowing the toy to evolve through software updates. The primary value of these devices is not their connectivity, but how they use data to facilitate complex play patterns that static objects cannot sustain.

The Transition from Mechanical to Connected Devices

The lineage of these systems began with simple mechanical automation, such as clockwork dolls or battery-operated cars that reversed upon impact. These were reactive but lacked internal logic. The introduction of low-cost microprocessors changed this dynamic, moving the industry from toys with fixed behaviors to toys with programmable states.

As microcontrollers became smaller and more efficient, designers integrated wireless protocols like Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE). This transitioned the toy from a standalone unit into a peripheral of a larger digital system. While “app-enabled” play dominated the early 2010s, modern systems are moving the logic back into the physical object to minimize screen dependency.

Analyzing the Historical Evolution of Smart Toys

The evolution of smart toys is not a linear path toward higher processing power. Instead, it reflects a series of experiments in balancing digital utility with physical engagement. Early novelty relied on the surprise of a toy “talking,” but as children became more tech-literate, engagement shifted toward agency and creation.

The Rise of Programmable Logic and Robotics

Early entry-level robotics kits, such as the original LEGO Mindstorms, were pivotal. They introduced the fundamentals of sequencing and conditional logic. For the first time, a toy functioned as a modular platform where the child acted as the systems architect. These tools were successful because they offered a “low floor and high ceiling”—easy to start, but capable of near-infinite complexity.

Robotic companions like those from Sphero further refined this concept. These devices moved beyond rigid building blocks into fluid, maneuverable hardware programmable through visual languages. They bridged the gap between a remote-controlled car and a laboratory instrument, making physics and geometry tangible through play.

The Limitations of Early App-Enabled Toys

The industry hit a bottleneck during the tablet boom. Many manufacturers created toys that required a constant connection to a screen to function. While this lowered hardware costs by using the tablet as the interface, it introduced a fundamental flaw: it turned three-dimensional play into a two-dimensional experience. Children often spent more time looking at the glass than interacting with the object.

This screen dependency created a cognitive disconnect. When the primary interface for a physical toy is a glass pane, the tactile benefits of play—fine motor skills, spatial perception, and sensory feedback—are diminished. Current design trends address this by making the underlying technology invisible to the user.

The Transition Toward Invisible Technology and Sensors

We are entering an era where hardware is sophisticated enough to hide. The next phase in the evolution of smart toys is defined by sensors residing inside familiar forms like wooden blocks or clay. This allows the child to remain immersed in the physical world while the computer operates in the background.

Eliminating Screen Interfaces with Embedded Sensors

Modern design aims to remove the screen as a middleman. Systems now use Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) or Near Field Communication (NFC) to recognize objects automatically. When a child places a specific figure on a baseplate, the system triggers a corresponding reaction without requiring a login or a digital menu.

By embedding Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs)—combinations of accelerometers and gyroscopes—toys now understand their position in 3D space. A block “knows” if it is being tilted, shaken, or stacked. This allows the toy to provide feedback through sound, light, or haptics directly from the object the child is holding, keeping their attention on their hands and environment.

The Mechanics of Smart Bricks and Tactile Feedback

Smart Brick technology integrates sensors into standard building block form factors. Companies like LEGO use these to track a construction’s progress in real-time. These bricks detect connections to other components, allowing a central hub to map the physical structure as it is built.

Haptic feedback—vibrations that mimic the click of a gear or a heartbeat—adds a layer of realism. When a toy pushes back against a child’s touch, it creates a stronger neurological connection than a sound effect from a tablet speaker. This sensory integration makes smart toys feel like living objects rather than digital gadgets.

Cognitive Benefits of Sensor-Driven Physical Play

From a developmental perspective, the evolution of smart toys toward physical-first interactions is a necessary correction. While digital literacy is important, the human brain learns effectively through 3D manipulation. Static screens provide limited input compared to the rich, multi-sensory data provided by physical objects.

Spatial Reasoning and Three-Dimensional Exploration

Research indicates that active construction and spatial play correlate with improved mathematical and engineering aptitude. Smart toys enhance this by providing immediate feedback. If a child builds an unstable structure with sensor-enabled blocks, the system can provide a subtle auditory cue. This allows the child to learn structural principles through trial and error rather than following a manual.

This type of play fosters computational thinking—the ability to solve problems through logic—without requiring code. Children essentially “program” their environment through the arrangement of intelligent objects. The system responds to their logic, reinforcing the relationship between cause and effect in the physical world.

Bridging Tangible Play with Computational Thinking

The industry is moving toward a hybrid model where toys track play patterns to adapt. If a child consistently solves a puzzle, an intelligent toy can adjust its internal logic to present a slightly more difficult challenge. This “scaffolding” is a core educational concept now automated by embedded AI, ensuring the child remains in a flow state where the challenge matches their skill level.

Privacy and Security in the Connected Toy Era

Integrating sensors into playrooms requires robust systems to protect users. In the evolution of smart toys, privacy is a foundational requirement rather than an optional feature. Because these toys may collect voice data or movement patterns, the architecture of data handling is critical for safety.

Data Collection and Edge Computing

The industry is shifting toward Edge Computing, which processes data locally on the toy’s internal chip rather than on a remote server. For example, voice recognition is increasingly handled on-device. This ensures that a child’s voice recordings never leave the room, mitigating the risk of data breaches or unauthorized surveillance.

Transparency regarding firmware updates and internet requirements is a key metric for evaluating toy safety. Parents and educators should prioritize toys with physical “off” switches for microphones and those that favor local storage over cloud dependency. This local-first approach preserves the benefits of smart technology while maintaining a closed, secure environment.

Establishing Industry Standards for Child Safety

Organizations are standardizing hardware security in educational technology. This includes encrypted bootloaders to prevent software tampering and secure pairing protocols for Bluetooth. As these toys enter classrooms, the vetting process used for tools like Arduino or Raspberry Pi is being applied to early childhood playthings.

Projecting the Next Decade of Physical Innovation

The future of smart play will likely move away from isolated features and toward broad capabilities. The era of the “gimmick” toy—one that performs a single trick and is quickly abandoned—is ending. The future belongs to modular, upgradeable systems that grow alongside the child’s developing skills.

Artificial Intelligence without Digital Displays

AI is increasingly used to facilitate complex storytelling. Imagine action figures that “remember” previous play sessions or a dollhouse that adjusts ambient lighting based on the narrative a child acts out. This uses AI as a creative partner rather than a screen-based distraction. Tools like Tinkercad already allow children to design physical components, and future modules will likely offer “plug-and-play” intelligence for these custom parts.

Modular Systems and Long-Term Durability

Sustainability is becoming a priority in toy design. The planned obsolescence common in the tech industry is a poor fit for toys, where durability is a primary value. The next decade will likely prioritize modular hardware, where the “brain” of a toy can be upgraded while the physical shell remains. This reduces e-waste and allows a single toy to remain relevant from toddlerhood through primary school.

The system of play is returning to its roots: the hand, the eye, and the physical object. The current shift ensures that while the objects become more capable, the primary experience remains firmly grounded in the physical world.